Birdcage

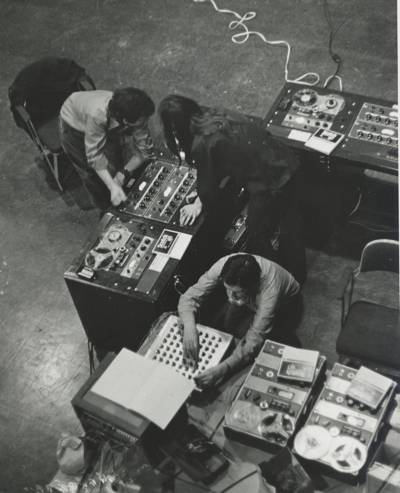

Joel Chadabe with student, John Cage at mixer performing Birdcage

David Tudor, Joel Chadabe, John Cage, Christian Wolff, Petr Kotik

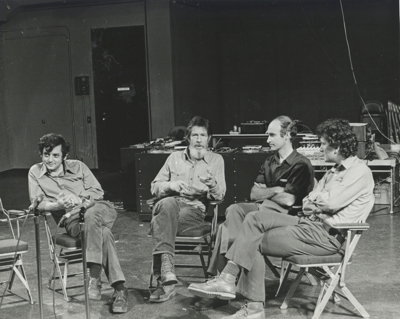

Conversation with the audience following the concert

Birdcage

This is the first several minutes of a Birdcage recording. The organization of sounds may change from performance to performance.

•

In early 1972, Cage composed Birdcage in the Electronic Music Studio at the University at Albany. I worked with him. Here is my account of it:

Cage arrived in Albany on a Monday night with Hans Helms, a German music critic and film director, and a film and audio crew of three people from the WDR. Hans had been commissioned to do a film of John composing the piece. John also brought three groups of prerecorded tapes: Group “A,” we’ll call it, was of singing birds which Cage had recorded in aviaries during the previous two weeks. Group “B” was recordings of John singing his own Mureau (an earlier piece based on Thoreau’s writings) in a chanting voice (as he observed: “It makes the birds seem less ridiculous”). And Group “C” was environmental sounds (the “wildtrack,” as filmmakers call it).

On Tuesday, we put the tapes in piles — A1, A2, A3 . . . and B1, B2, B3 . . . and so on — and set up eight source tape recorders, continually playing, routed through a mixer to one destination tape recorder. John was sitting in the center of the studio, looking at the studio’s digital clock. According to a timing chart that he had prepared Monday evening, he would say, for example, at a particular time: “Put tape C3 on tape recorder 7,” and we would do it; and he would say, for example, at a particular time: “Now switch to tape recorder 5,” and we would get ready, he would give a hand signal at the very instant that this was to be done, and we would at that signal change the settings on the mixer so that whatever sound was at that moment being played on tape recorder 5 was routed to the destination tape recorder.

At different times throughout the day, according to his instructions, we would change the tapes being played on the source tape recorders; and at random time intervals measured in seconds — an interval of approximately five seconds, for example, might be followed by an interval of seventy-two seconds — we would change the settings on the mixer to route a new sound group to the destination tape recorder. In this way all of the Group A, B and C tapes were sampled, in random order and in random durations, onto what turned out to be twelve single tapes. Those tapes functioned as “submasters.” They were yet subject to another series of operations, scheduled for the following day.

Wednesday, however, was wasted because of misunderstandings between myself and John as to what was technically possible in the studio and what we needed to do. After a frustrating work session, everyone came to my home for a dinner party, which was jovial and funny. I thought to myself, “What happens when we have a good day?”

On Thursday, we processed the sounds from the submasters. The tapes were in turn played back through filters, ring modulators, and other audio processing devices, according to a time chart that John had prepared after dinner the previous night. We set up a routing system such that each submaster tape, played back on one source tape recorder, could be routed by switching through any of the various processing devices to a single destination tape recorder. One after another we played the submasters and processed them. Again, John was sitting in the center of the studio, watching the digital clock as he followed his time chart, this time calling out, for example, “Now, ring modulation,” and we would switch from whatever processing device was currently being used to the ring modulator. Since the audio processing and the amount of time that each type of audio processing was used were determined by chance, the processing was completely independent of the sounds that were being processed. We had no idea as to results until we heard them. Sometimes John would say something like, “That’s absurd.” Sometimes we would all laugh. Sometimes we were delighted.

Shortly after the composition was finished, John had a friend in Switzerland who built an 8-in 8-out mixer so that any of eight inputs could be directed, together or separately, by a single performer, to any of eight outputs that directed the sounds to loudspeakers in places around the concert hall.

The first performance took place on December 9, 1972, in a theater at the University at Albany. John and I arranged the loudspeakers and chairs. We performed Birdcage while David Tudor simultaneously performed Monobird. Christian Wolff and Petr Kotik came to Albany to hear the performance. The local audience was a group of Albany-based artists, faculty, and interested students.

During the next few years, I went with John now and then to oversee and perform at concerts mostly throughout New York, city and state, in concert halls and galleries. Either of us, in turn, would push buttons on the mixer in any group or order, creating in sound, as John said, “a space in which people are free to move …”

— Joel Chadabe

•

One day in 1972 John Cage dropped by C. F. Peters, excited and amused that he had discovered – quite by chance – a beer coaster with the colorful orange, black and white design of a bird cage, complete with singing dove. Headed toward a favorite Philadelphia haunt, the Walnut Street Bookstore, he had found the coaster in a downtown working class bar, “The Bird Cage,” in all probability an unlikely starting point for musical inspiration. But associations of birds and Cage and cages had always fascinated him. Would Peters obtain the rights to include the bar’s coaster in the score of a tape composition then being composed with the assistance of Joel Chadabe? The puzzled owners of the Center City establishment speedily and unhesitatingly granted permission to his publisher. “Hey Louie, you aint gonna believe what dese people up in New York want.”

On December 8, 1973, Bird Cage received its New York City premiere as the conclusion of “Two Evenings of John Cage” – concerts designed by Jim Burton and myself to inaugurate the Kitchen at its new home at 59 Wooster Street, and to imprint on the fledging organization an aesthetic orientation. Connie Beckley, Rhys Chatham, Philip Corner, Jan Coward, Jon Deak, Garrett List, Larry Nelson, Phill Niblock, and Judith Sherman were only a few of the performers associated with these memorable Cage events. Joel Chadabe supervised the installation of the 12 Bird Cage tapes, which provided the musical setting for a feast of sautéed mushrooms fresh from the Essex Street Market, and for a high-spirited party, whose members included Cage and many of his friends from the art, dance and literary worlds. Drinks were served on dozens of Bird Cage coasters kindly supplied by the Philadelphia tavern for “promotion.” There were alas no live birds inside the Kitchen’s large space, even though Cage meticulously included his National Audubon Society membership card in the published score!

In Philadelphia some months later, I visited the rundown bar on Ninth Street, and, while a stripper performed with obvious boredom in the background, I thanked the bartender for his assistance in the recent concerts. “Hey Louie, you aint gonna believe what dese people up in New York did.” The Bird Cage closed its doors about the time America celebrated its Bi-centennial, and John Cage is no longer with us. But Bird Cage lives vividly in the present, and memories of a wonderful musical and social evening in “a space in which people are free to move and birds to fly” linger among many grateful people.

— Don Gillespie

•

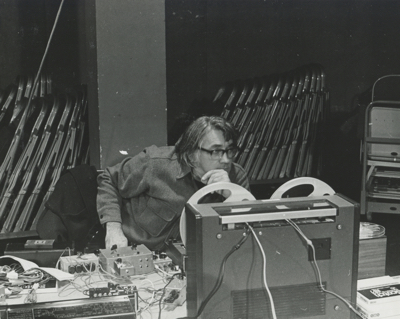

David Tudor performing Monobird

Joel Chadabe, John Cage, Christian Wolff, Petr Kotik

Conversation with the audience following the concert